Resercher Interviews Asst Prof. Agulto Verdad Canila

What is your research topic?

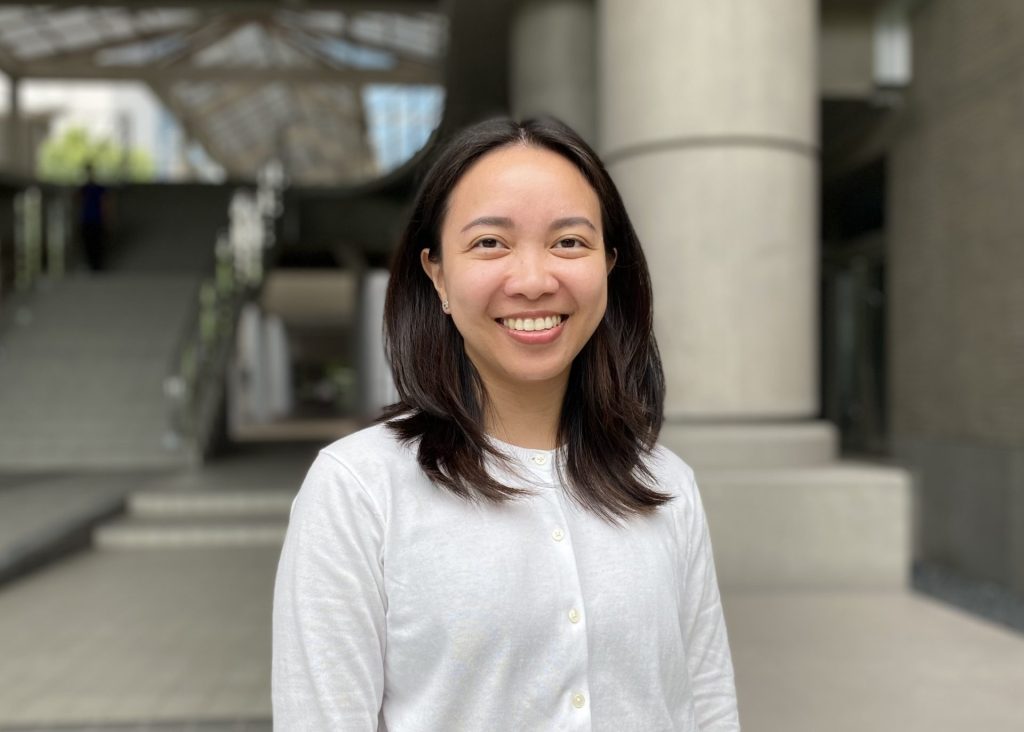

My research is all about using a particular kind of light, called terahertz waves, to study emerging materials. Although not as commonly known, terahertz waves are part of the electromagnetic spectrum and lie between microwaves and infrared light. Just like X-rays help doctors see bones, or visible light is used in microscopes, terahertz waves allow us to explore the properties of materials through a technique called spectroscopy, which is simply the study of matter using light.

Although not as commonly known, terahertz waves are part of the electromagnetic spectrum and lie between microwaves and infrared light. Just like X-rays help doctors see bones, or visible light is used in microscopes, terahertz waves allow us to explore the properties of materials through a technique called spectroscopy, which is simply the study of matter using light.

To build new technologies and develop new applications, scientists and engineers need a deep understanding of how new materials behave. In my research, I mostly use terahertz spectroscopy to study semiconductors, which are the building blocks of modern technology. With the rise of artificial intelligence, the role of high-performance and more efficient semiconductors is becoming even more important. Using terahertz spectroscopy, I investigate how charge carriers (electrons or their positive counterpart called holes) move through these materials, which is essentially how electric current flows. These insights help determine how suitable a material is for things like faster computers, better sensors, or more efficient energy devices.

How and why have you chosen your research topic?

When I was a master’s student, I became interested in materials science. It’s an interdisciplinary field that involves studying the relationship between a material’s structure, properties and its applications, with the goal of understanding, improving, and even creating new materials. I started working on a semiconductor called zinc oxide, which emits ultraviolet light, and studied how we could tune its emission properties. At that time, aside from synthesizing and optimizing the material myself, I was also analyzing it using photoluminescence spectroscopy, which involves ultraviolet and visible light. That marked the beginning of my research involving the spectroscopy of semiconductors.

Later on, through collaboration with researchers from other fields, I was introduced to terahertz spectroscopy, which gave me a new way to study semiconductor materials. It’s like looking at the same object through a different filter—the filter we use changes the way we see things. With terahertz spectroscopy, I’m able to “see” another side of materials in a way I hadn’t seen before.

What are some of the results of your research?

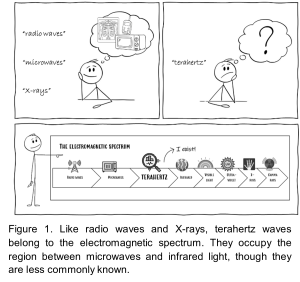

Together with colleagues and collaborators, we have uncovered some of the fundamental properties of next-generation semiconductors, such as gallium oxide, silicon carbide, and gallium nitride, using terahertz spectroscopy. For example, we measured the relative permittivity which is a key parameter for developing semiconductor devices.

We are also advancing an emerging technique called terahertz ellipsometry, which enables spatial mapping of material properties across semiconductor wafers. This approach is especially useful for evaluating materials that are opaque to terahertz waves, and we believe it holds strong promise for practical applications in the semiconductor industry.

What do you find difficult or challenging about your research?

One of the challenging aspects of my research is working with spectroscopy setups, which involve lasers, lenses, and mirrors that guide light to specific paths. These optical elements must be arranged and aligned with high precision, and learning how to do this properly takes a lot of time, experience, and patience. What makes it even more difficult is that terahertz waves are invisible to the human eye, unlike visible laser beams. This means you can’t easily see if the terahertz beam is going where it’s supposed to, so adjusting and optimizing the setup becomes more complex. It’s like trying to take a sharp photo with a camera that’s out of focus. No matter how interesting the subject is, the image will always come out blurry unless the lens is properly adjusted. In spectroscopy, if the optics aren’t aligned correctly, the measurements won’t reflect the true properties of the material we’re studying.

Please share a message for younger students who aspire to become researchers.

I know that becoming a researcher isn’t always seen as the most popular or obvious career path. But I hope young students can see that it’s a valuable and meaningful one. The technologies and knowledge we have today were built step by step through years of research by many scientists before us. Research is like a relay race, and each generation passes the baton to the next. That’s why we need young students who are willing to take up the baton, to keep asking questions and looking for answers that might someday help improve our society. If you’re someone who’s curious or who enjoys understanding how things work, research might be something worth exploring.